Robe bleue

— for Hélène Bessette

I can’t be sure if I wore it for Hélène Bessette or for my own seduction. I wouldn’t have said that my mission was to beguile anyone, not really, and especially not my favorite French writer, who has been departed since 2000. Yet, on April 27, 2023, I felt a deep honorific swell for her and thusly thrust my head upwards into a blue dress.

A dress is a funny piece of clothing, a kind of spell for the body or a curtain for the soul. I’ve never put on one that hasn’t sparked a kind of a conjuration. After all, the cut of the garment itself implies the trace of another woman. As I walked up to the top of 24 rue de Regard, the address where Bessette wrote Le Bonheur de la nuit, I was enacting a kind of séance, as if this day was when I would be the closest to her spirit.

--

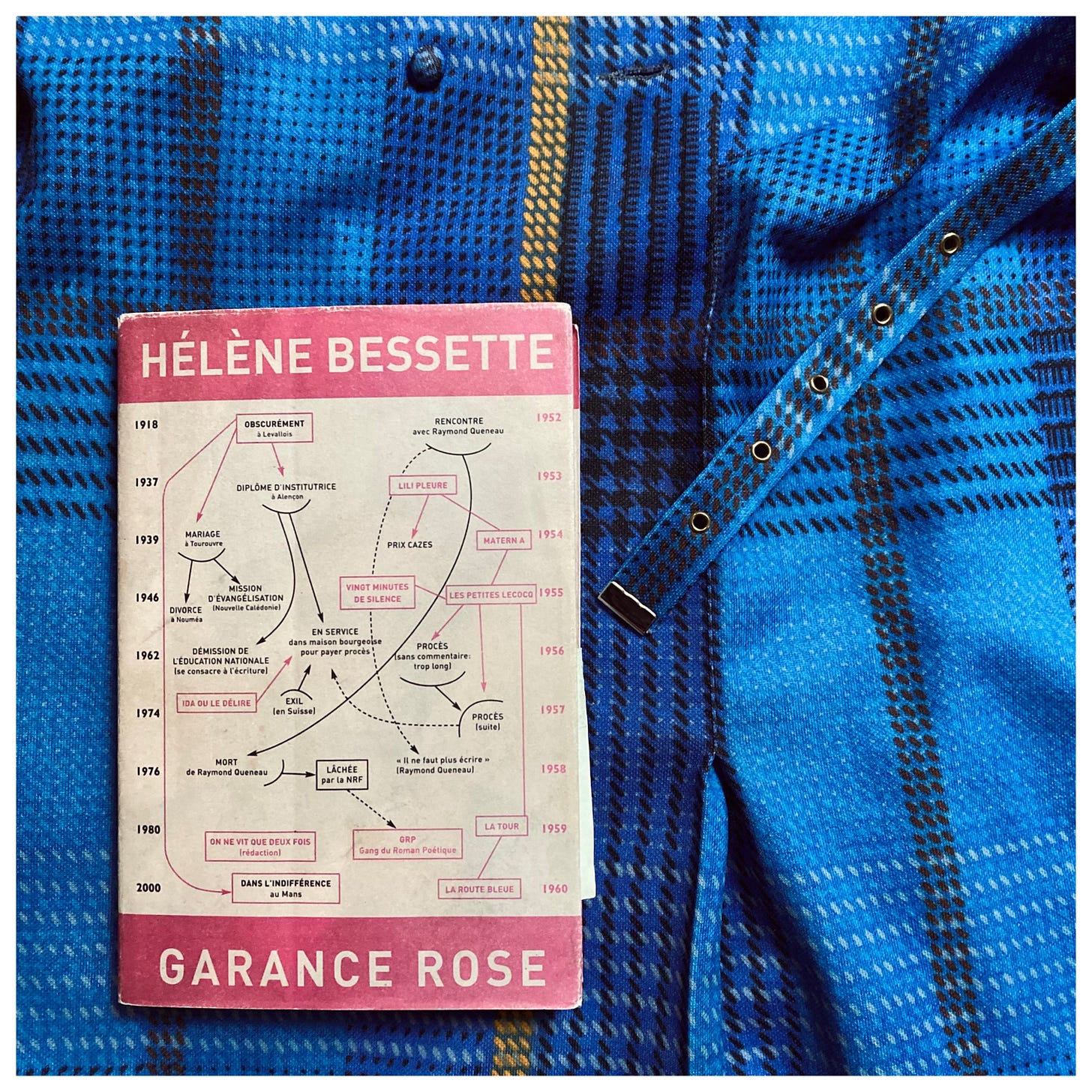

For six years, I had been loving this woman. When I finished my first reading of Garance Rose, her 11th poetic novel which was published in 1965 by Gallimard and reissued in 2017 by Le Nouvel Attila, I was so fully enamored that I couldn’t put it down. If I could have worn the text on my body, I would have. For days I kept it against me, tucked carefully into the left side of my satchel so as to hug my side or gripped tightly to my chest as I moved about my apartment stations, resting it on a nearby surface only to avoid compromising the cover with my sweat.

I had never read anything like her before. Her lines were crisp and incantatory, and my lips chased their phrasal footfall. I was intrigued by the book’s structure, how it riddled and turned every binding agreement — between state and citizen, board of education and teacher, author and reader — on its linguistic head to render it relationally abstruse or defective. And while the plot elements, if Bessette could stomach such a term, were rather incongruous with my own reality, I felt emotionally allied to this mysterious school teacher, this lone woman, this Rose de Garance.

The novel opens with an unforgettable line — L’héroïne est absente.“ The heroine is missing.” — and reminds Bessette’s readers of her common mission: to write novels not as a mediator of norms but as a challenger to the form, playfully if not inhospitably complicating narrative expectations. In fact, dislocating a novel’s heroine, making her absent or dead or away in Switzerland, is kind of Bessette’s thing. In Rose, the missing heroine is a teacher; who having not properly satisfied the role of obeying, sacrificial woman; is being made to answer for society’s dark imaginations of her. C’est une femme qui s’amuse. “She’s a woman who likes to have fun.” The entire plot builds on rumors, anonymous accusations, and puzzling classified documents, and the readers are left to track the clues, hover on the edge of the mob, at once sequestering in registers of metafiction and falling themselves prey to hearsay. For six years, I’ve been thinking about this missing woman, this teacher who was stalked by the insatiable regard of an administration so convinced of its propriety it could invent her criminality.

--

I was getting dressed at all because I was attending the unveiling ceremony for Bessette’s memorial plaque, and, in thinking of this missing Garance Rose who had been shuffling through the classrooms of my mind, I searched my closet for what felt like a teacherly dress. This is my teaching dress is what I had told myself when I found the “Marcelle Griffon” at Ding Fring in the 20th. It was hanging there, a strict, conservative, synthetic thing. I liked its small buttons that rose up the bust and its little metal-tipped belt. I liked the funny 70’s plaid graphic pressed upon it. But its hue gave it away, told me about the woman inside who drifted away.

--

I have always felt deep down that I am a lone woman. Surely, I love my people — my family, my friends, my fellow poets, my students and colleagues — but for the longest time I was told to temper my independence. Now, I know how to sail away in my head and keep my feet planted, or so I believe. In the past, my need for space and autonomy had scared my parents, lovers, and friends. Some have told me, from time to time, that I could be right in front of them but traveling elsewhere. Some have told me that I can feel absent, gone. Missing? And yet, I have shore. I do come back. Rather fiercely and with a message that makes my companions know I wasn’t really so far away. That I have kept them with me, wherever it is I went to.

The blue dress seemed to encapsulate something of that spirit, my spirit, my fastening and unfastening. Like so many artists, I have a thing for blue. If I return to it, this is my teaching dress seems at once an absurd thought and also a right one. I do see the “Marcelle Griffon” blue dress combining worlds, letting me be present for my students and continue my necessary intellectual voyages, letting me live my present but also dislocate to other times, to other cloths of other teachers crafting their inner universes.

I come from a good helping of women educators. My mother taught for 37 years in Alabama public schools. My grandmothers. My aunt. My cousins. In my family, education is a renewing profession, a kind of endowment, so I know what a teacher’s world means. I know that you can be revered as near-saint. I know that it consumes your life, your dreams. I know that teaching is an everyday visitation of your own educational successes and woes, and if it’s not, then you’re probably not a very good teacher. I know that you are not allowed to be your own, that privacy is practically an interdiction. Perhaps that’s why, given my legacy and heresy, I’ve entered the profession as transient. I will always forever and foremost be a linguistic traveler, a poet, which means that in the classroom, I will be made to answer for the part of me that is “not fit” for the classroom. Believe me, I’ve been asked uneasily about my “artistic side” in almost every interview for a permanent teaching position. A woman qui s’amuse, however she wants, is still seen as dangerous.

--

I was one among maybe forty there to celebrate the memory of Hélène Bessette. As I listened to her younger son Patrick say something like, Derrière son chignon, elle a combattu des conventions, I thought of the ways, Bessette, former schoolteacher, had worked a lone woman magic, how even in the company of students, under the surveillance of school board, she had been voyaging to her art space, hosting intellectual revolution right before their very eyes. I thought of for how long a dress has been the cloak of that, the woman rumbling underneath. As they pulled the blue, white, and red material away from her name, away from her now immortal title, romancière, I made a promise to Bessette from the depths of my blue teaching dress.

Loved reading this! Very thought provoking. Need to read her books.

A beautiful testimony to the unexpected ways we find connection to others. Your words give such dimension to the fabric of a dress!